Pergolas and trellises – a short history

This story starts with the most famous of gardens, Paradise, our first ever garden, created when history itself was born out of light. And what a garden it was! Aptly named ‘The Garden of Eden’, which is Hebrew for ‘pleasure’, it must have been a garden for all of the senses, at once luxurious and playful, stirring the desire which drew Adam and Eve together in that first attraction of opposites in the story of humankind. At Classic Garden Elements we imagine that the Garden of Eden surely featured an impressive array of pergolas, arbours and trellises. Alas, we still lack definitive proof, but this perhaps is a fruitful field of research for religious scholars – and indeed for gardeners.

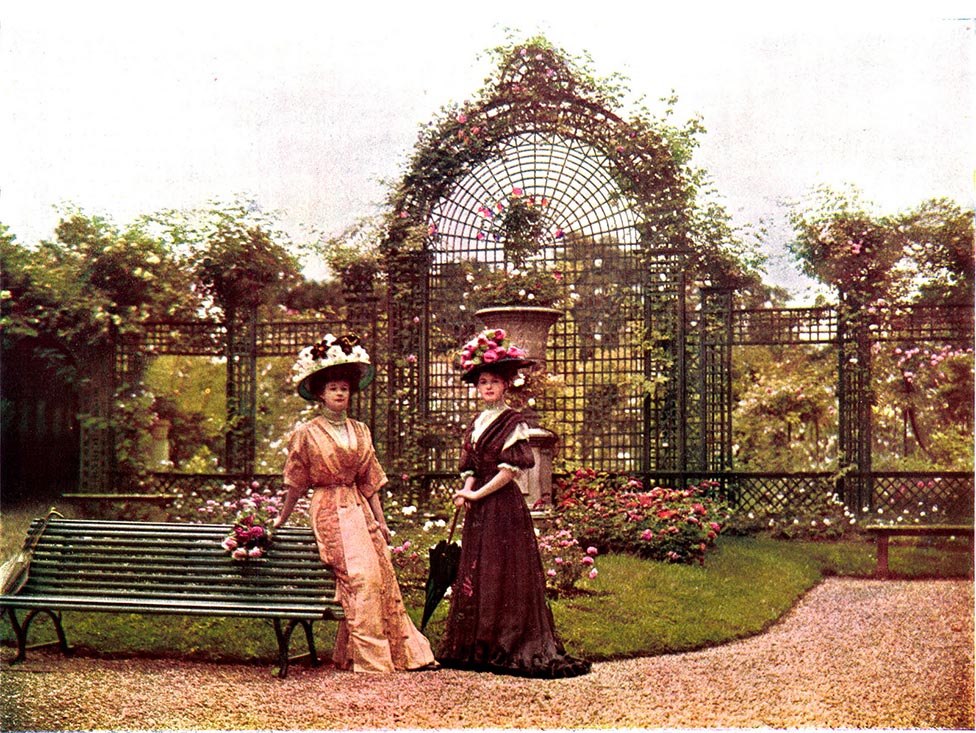

Happily, we know more about the gardens of ancient Greece and Rome, where vine-entwined trellises abounded, hands were held beneath pergolas, and shy kisses exchanged in rose-covered arbours. Katherine Swift, renowned author of ‘The Morville Hours’, and a leading gardener and garden historian, shares her reflections on the history of these ancient and delicate structures.

´

Playful movements of light and shade

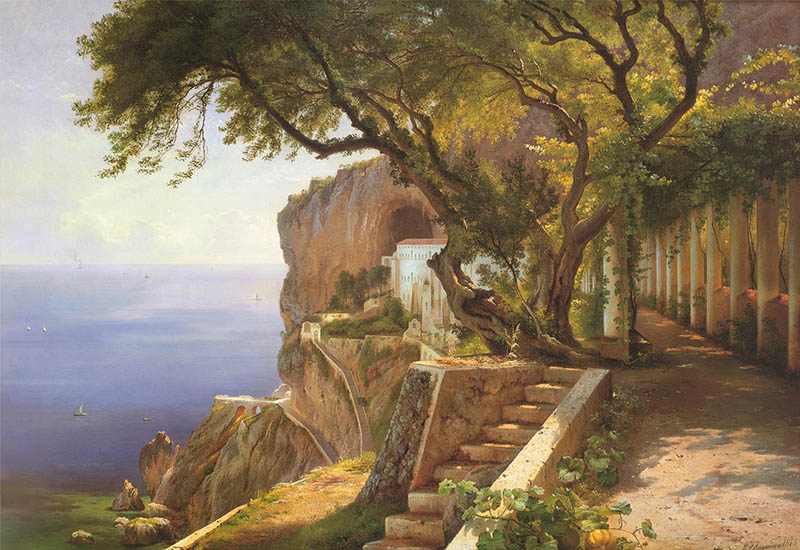

Pergolas, arbours and arches are a source of some of the most acute of all garden pleasures – the visual contrast of architectural line with twining plant, the gardenly satisfactions of plants trimly tied and trained (or wantonly trailing), the sensous dangling of fruit or flower just within reach – but above all perhaps, of the subtle interweaving of interior and exterior, the special feeling afforded only by structures like these of being both inside and outside at the time.

The experience of walking, sitting beneath such open plant-covered structures is qualitatively different both from the experience of sitting beneath or among trees, and also from the sensation of being within a more solid structure or building. Inside a pergola or an arbour, we are not removed from the sights and sounds and smells of the garden outside, the playful movement of light and shade, the touch of breeze, the passage of the clouds overhead – indeed we experience all these things with a sort of heightened consciousness, as if the framing device of the structure called our attention to what before was mere vacant air.

Structures inviting our participation

Yet always there is that delicious sense of enclosure. These structures invite our participation in the garden: they beckon us to enter, to stroll, to sit, above all to linger. Time slows to a languorous drawl in structures like these. Sitting in a garden without some feeling of enclosure about one is somehow unsettling and unsatisfactory, like sitting in a room without an open fire: we never stay long, never quite settle down to the book or the unwritten page, which glares whitely at us in the plain light of day.

Similarly, there is never quite the same feeling of intimacy and ease in a stroll à deux out in the open as there is down the long vista of the pergola. And to dine without benefit of the dappled shade provided by pergola or arbour feels somehow perfunctory and spartan, however glorious the weather.

From King Ashurbanipal to Gertrude Jeckyll

The appeal of such structures is universal and timeless, spanning continents and millenia. And almost from their beginnings in ancient times, their frank appeal to our sensuality has been well to the fore. Some of the earliest representations of structures such as these are used to frame scenes of eating and drinking: Greeks and Romans sprawl on their dining couches, the Abyssinian King Ashurbanipal feasts with his queen beneath an arbour of vines, waterside revellers in the Alexandrian resort of Canopus loll beneath ripe grapes and perfumed roses.

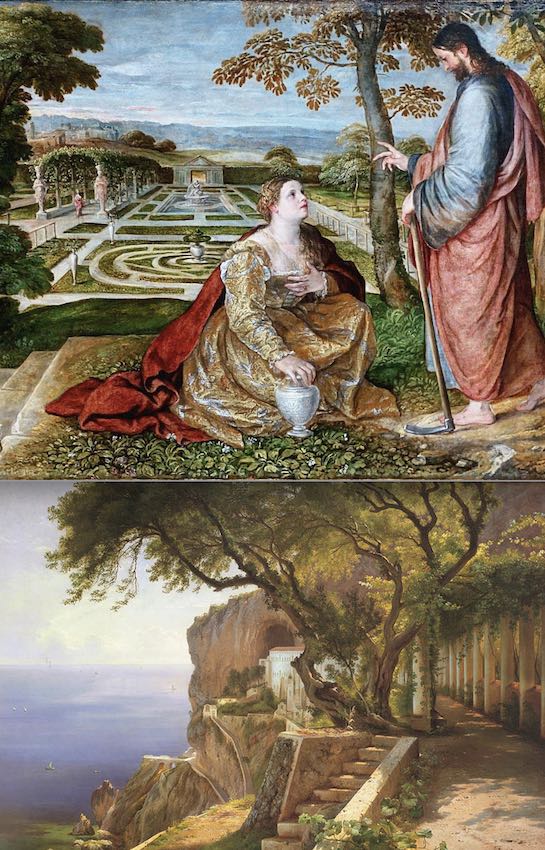

In the third century AD the Roman writer Achilles Tatius commented on the effects of light and dappled shade, the delicious interplay of cooleness and warmth on the skin – an effect carefully stage-managed by Gertrude Jeckyll sixteen centuries later. And for centuries their decorative appeal has attracted artists as well as gardeners, exploiting the piquant contrast between architectural elements and the soft twining counterpoint of the plants in art works and artefacts from Greek urns to Pre-Raphaelite fabrics and wallpapers.

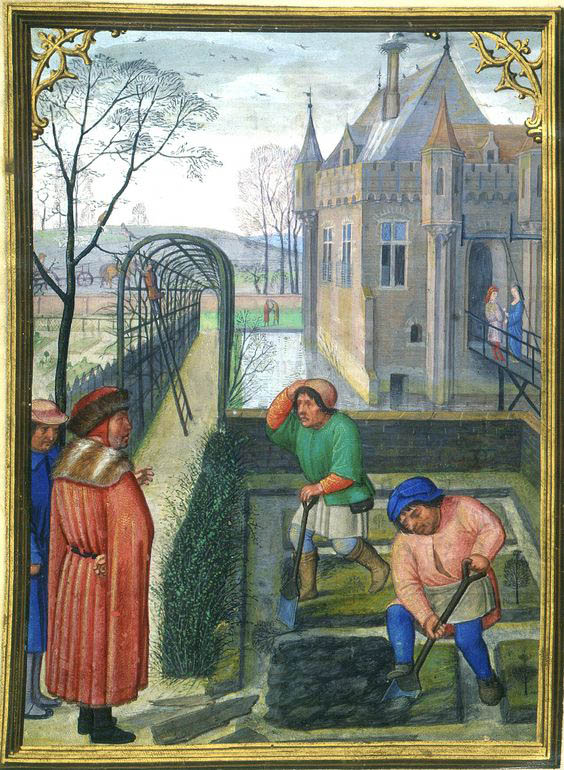

Madonna and Child

In medieval Christendom, arbours of all sorts gained an added spiritual dimension as a setting for representations of the Madonna and Child, both bringing the holy figures into the real world in an everyday setting, and in turn enriching the everyday world with the consciousness of the glories of God’s creation. In the symbolism of paintings such as Cranach’s Madonna in the vine arbour, viewers were invited to see the partnership of God and man, paralleled by the partnership of architecture and plant, gardener and nature.

Beauty and Utility

A constant theme is the combination of beauty and utility. With their origins in the ancient cultivation of grapes, such structures were soon adopted as supports for a variety of other climbing plants. Vines and roses were a common combination from ancient times, and many a modern structure has reclaimed for us the decorative possibilities of fruits and climbing vegetables as well as flowers. But beyond their merely horticultural role, pergola-like structures in particular have always fulfilled an important circulatory function in linking (or sometimes separating) the different parts of a site, whether medieval European monastery or castle with its covered walks linking different buildings, Chinese garden with its elaborate open-sided lang, or twentieth-century western compartmentalised garden with its pergola or arch pointing the way from one garden ‘room’ to another.

In contemporary western usage designers have continued to play with ideas of time by making pergolas and arbours on the one hand from dynamic, sustainable structures of living wood such as willow, and on the other hand from materials such as stainless steel, left unplanted. Open plant-covered structures in contrast respond to the time and the season like the garden itself, the plants burgeoning into leaf, flower and fruit before fading or lapsing back into winter sleep, the structures themselves gently decaying. They are in themselves little essays in mutability.

Essays in mutability. Powerful feelings of transitoriness

Some of those structures are closer to solid garden buildings, where we find an interior unvaryingly the same within a structure built to last: damp-proofed, roofed over, sometimes walled in. But the pergolas, arbours and arches of which we talk here all convey powerful feelings of transitoriness, movement, a sense of the fleeting moment. In certain cultures the plants may be chosen to heighten that sense of transience, as in the traditional Japanese use of wisteria with its fragile fleeting blossoms so transparently at the mercy of frost and rain, tossed by every gust of wind. Elsewhere plants have been chosen in an attempt to deny that essential fact, as in the seventeenth-century European fashion for tunnels and arbours made from clipped hornbeam – the plant becoming the architecture while the architecture, in the form of ever more fanciful trelliswork, stood alone as an ornament in itself.

History and Aging in Dignity

With the passing of seasons, a layer of pollen and algae gathers on the surface of our ‘Classic Garden Elements’ structures, so that over the years, indeed decades, an unusually attractive patina is formed. The Arches, Pergolas, Treillages, Arbours and Pillars made by Classic Garden Elements weather and age with that unique dignity inherent to Greek and Roman ruins while their inner stability is guaranteed by hot-dip galvanised solid steel.

Andrew Marvell (1621-78) wrote two famous lines about these topics:

Annihilating all that’s made – To a green Thought in a green Shade